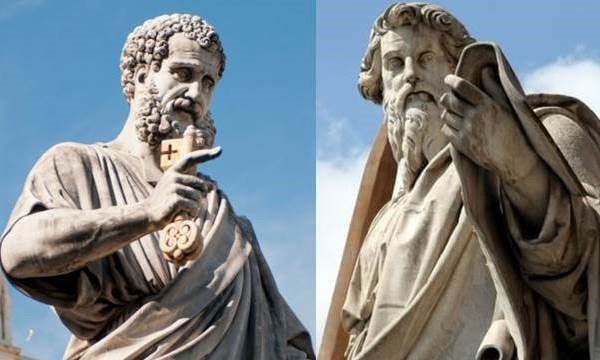

Cycle A | SOLEMNITY | SAINTS PETER AND PAUL, APOSTLES

REFLECTION

– By Fr Ugo Ikwuka

Archway, London

This Sunday, we commemorate two of the great New Testament heroes, the apostles Peter and Paul. They were both gifted Church leaders but the differences in their personalities meant that they didn’t always get along with each other. Paul was a first class graduate of Law and the Scriptures. He was very fluent in Greek and possibly Latin. In contrast, Peter had no formal education. He was a local fisherman. He was simple and kind-hearted and had the privilege of knowing Christ personally and working alongside him.

They were however united in their common humanity and flaws. Peter loved Jesus and wanted to please him but when push came to shove, he lets Jesus down badly as happened in his denial of Jesus at the moment of truth. He is also impulsive; acting before thinking. After the death and resurrection of Jesus, he naively goes back to his fishing; a disappointing response to those momentous events. Paul, on the other hand, was a notorious persecutor of Christians. He was present at and entirely approved of the stoning of Stephen. He has something of the fanatic about him.

Yet, God has a way of choosing people who are completely unworthy to carry out his plans for the world; Moses and David are some of the other examples. And one reason for this is to demonstrate that the way of salvation is open to all. With the Pentecost (Peter) and the dramatic encounter on the way to Damascus (Paul), the trajectories of their lives were completely changed such that with outstanding courage and faithfulness, they both in their different ways consolidated the Church, enabling it to make rapid progress in those crucial early days. They both ended up in Rome where their efforts to spread the faith led them to suffer a martyr’s death.

A read through the Acts of the Apostles, the Letters of Peter, Paul and James and the first three chapters of the Book of Revelation shows that early Christians had their conflicts. The everyday life experiences in their local churches were much the same as our experience of church life today with its frictions. The differences in the personalities of Peter and Paul, and their approaches to issues reflect these frictions. In Corinth for instance, the Church was divided into rival parties depending on who was preferred between Peter and Paul.

Later, the two had a serious row in Antioch concerning whether Jews who became Christians should be allowed to retain some of their Jewish traditions like having a separate Passover meal. While Paul insisted that the Jews and Gentiles should eat together so as not to divide the body of Christ, Peter felt genuinely concerned for those Jewish Christians for whom it may be too much to abandon all their lifetime habits on becoming Christians. So, in a moment of empathy, Peter agreed to eat separately with the Jews which led to this quarrel with Paul.

You can therefore see how, acting from the best of intentions, Peter and Paul felt let down by each other. It was many years before they made up their differences. Tensions like this have always been part and parcel of the Christian Church. Much of the division among Christians stems from groups of Christians idolizing their favourite leaders and putting them in the place of Christ as happened in Corinth (1 Cor. 1:10-17). Of course it is inevitable that certain Christians would feel more at home with the dogmatic security of the keys of Peter (Matt. 16:10-19), others with the charismatic liturgy of Paul (1 Cor. 14:18).

On the one hand, there are those who will like the Church to be welcoming of people of different persuasions, even with some of their cultural heritage. Perhaps a modern example would be Pope Benedict’s accommodation of disaffected Anglicans under the Ordinariate whereby they still retain some of their Anglican traditions while they were received into the Catholic Church. Of course some people kicked against this, imagining that if the deposit of the faith is with the Catholic Church, then, that truth should not be compromised in the cause of being kind or inclusive. It is either you are in or you are out.

It is also possible that in our local Churches, there will be preferences along cultural lines. Once, a parishioner complained that there was too much singing in a Sunday Masses. Yet, some other parishioner had commended the singing at that particular Mass. The person who wants a quieter Mass is not wrong, and could even find support in Psalm 46: “Be still and know that I am God.” On the other hand, the person who wants to sing and even dance is not wrong either, and could equally find support in Psalm 100: “Come before the Lord singing for joy.” So each side has their arguments.

By celebrating the feasts of the apostles Peter and Paul together, the church is teaching us to look beyond our differences and recognise that we are first and foremost followers of the one Lord Jesus Christ and children of the one Father, God. If we recognise this every day, there won’t be that mindset of them and us which undermines the Christianity we profess. Christian unity is not uniformity but unity in diversity. That is what many churches today celebrate at Pentecost, beautifully expressing cultural diversity in liturgy, outfit and in the meals afterwards – a foretaste of heaven.

Hopefully no one feels uncomfortable with such celebration of diversity or they will feel uncomfortable in heaven where the one culture is love that embraces all. Yet, this legitimate expression of diversity, should never lead to division (schism) because, as Paul reminds us, what unites us as Christians far outweighs whatever it is that divides us (1 Cor. 1:13).