Cycle A | ORDINARY TIME | WEEK 29

REFLECTION

– By Fr Ugo Ikwuka

Archway, London

If someone asks you, “Have you stopped stealing?” You wouldn’t give a direct ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer without implicating yourself because the question presupposes that you have stolen before. Because it is ‘loaded’ with questionable presumptions, such questions are faulted as fallacies in logic. Like a loaded gun, such loaded questions are dangerous. The way to approach them therefore is not to answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ but to challenge the assumptions they make.

The Pharisees posed such ‘loaded’ question to Jesus in today’s Gospel. They ask him if it is lawful to pay taxes to Caesar. To put the question in context, the Pharisees advocate strict adherence to the letters of the Law while, on the contrary, Jesus stands for the spirit of the Law which is love of God and love of neighbour. Thus, Jesus and the Pharisees are always at loggerheads and they seek every opportunity to discredit him.

Their malice is clear in the delegation they sent to question Jesus; a mixture of their disciples and some Herodians. While the Pharisees were conservative Jewish nationalists totally opposed to the Roman colonial rule under the Emperor Caesar, the Herodians were a more liberal Jewish sect supportive of the King Herod who is loyal to Rome. Both sides therefore hated each other but in Jesus they have a common enemy. The nationalist Pharisees oppose taxes to the oppressive Roman colonial government. So, in the presence of the pro-Roman Herodians, they maliciously ask Jesus if it is right to pay taxes to the Roman Emperor.

If Jesus says ‘no’, he will have pleased the Pharisees but both camps will report him to the colonial authorities for sedition and inciting opposition. If he says ‘yes’ he might please the Herodians but would lose credibility with Jewish patriots who will consider him a traitor. Jesus deftly evades the wicked trap. When they produce the coin with Caesar’s image on it, he says to them: “Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s.”

Before we consider the implication of that response, this encounter helps to highlight the meanness of some religious people which has persisted over time. Rather than be open to dialogue, people try to destroy those with different religious opinions. Such hatred is seen not just between religions but also within religions and denominations. Growing up in south-eastern Nigeria, one hears, as a mocking catechism asks, “Will Protestants ever go to heaven?”, the answer: “Yes, but by the skin of their teeth.”

At denominational level, conservative and liberal Catholics are pouring venom on each other in the social and print media. But you can’t serve the God of love by hating people. In the very act of doing that, you undermine the God you claim to proclaim. This is the problem with the Pharisees, and Jesus sees through their malice. He knows that they are not questioning sincerely about church and state relations so he doesn’t play the game. A sarcastic response to religious haters is therefore allowed!

Yet, Jesus wasn’t merely being cynical or craftily responding to evade a trap. His response is pertinent for church and state relations. It makes clear that the state has a legitimate sphere of influence. We all, for instance, largely depend on the state for social services and infrastructure: water, electricity, education, healthcare, roads and other welfare services. The maintenance and improvement of these services also depends largely on the cooperation and support of the community. And we do this mostly through paying taxes.

Hence, taxes are not just “necessary evils”. In a just system, they are our contribution to making the services we take for granted available. In a just tax system, we also help to spread more evenly the wealth of the community so that each one has access to what they need for a life of human dignity. A state is therefore deserving of loyalty to the extent that it meets her obligations to her citizens. That is the import of Jesus’ statement that Caesar should be “given back” his due. In other words, a government should get, not a blind or absolute loyalty, but what it deserves.

Isaiah, in our First Reading, refers to Cyrus, a sixth century B.C. pagan Persian king as ‘messiah’ (anointed one) which strongly underlines God’s sovereign liberty in employing whichever human agents he chooses in history. Cyrus was an outstanding figure ruling over a vast empire. He was an exemplary king who respected the customs and religions of the lands he conquered. His government worked for his subjects. His edict of the restoration authorized and encouraged the Jews exiled by Nebuchadnezzar to relocate to the Land of Israel and actively engage in rebuilding the Temple destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar.

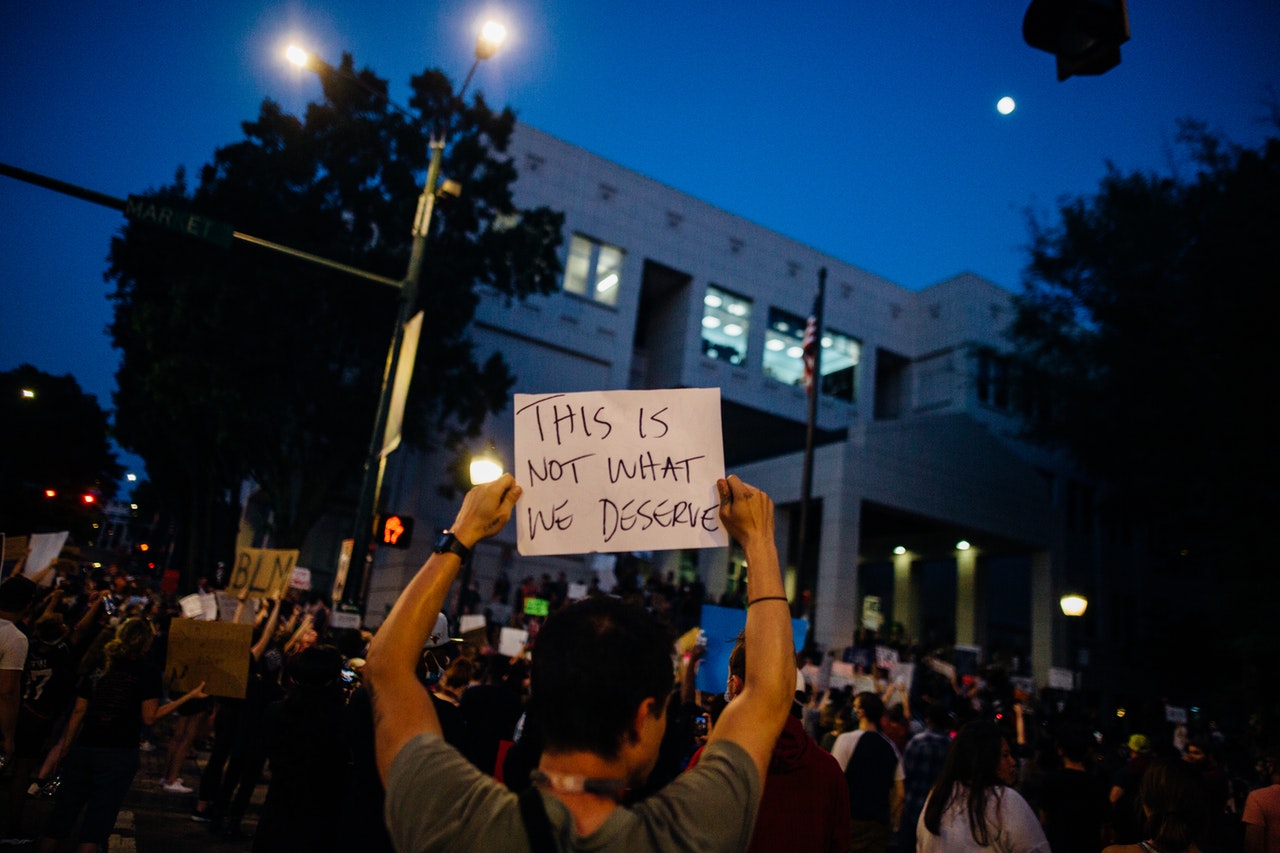

The principle of justice does not demand that people give their loyalty and support to a corrupt or self-serving government. In fact, people can only give back their frustrations to such governments. In the United States, both black and white people violated the segregation laws operated in many states. In South Africa’s apartheid system, many Christians were forced to violate the immoral laws of their government. To be a Christian disciple in our time and place means that we ought to be aware of what is going on in our social system and may have to stand in strong opposition to the authorities on certain issues, for instance when they promote anti-life policies.

Ultimately therefore, civil authorities are subject to the higher demands of truth and justice, and the inviolable dignity of the person. In other words, they are subject to God in whose image we are all made and to whom everything belongs including Caesar. Where our loyalties to the civil authorities and to God are in harmony there will be no conflict. But wherever people’s rights and dignity are undermined, conflict is inevitable. Yet, such conflicts are not always bad; through creative conflicts, the flawed kingdoms that men build can, in time, become the Kingdom of God.