CYCLE C . LENT . WEEK 6. HOLY WEEK – MAUNDY THURSDAY

REFLECTION

– By Fr Ugo Ikwuka

Archway, London

Traditionally, when the head of the family is about to die, he would normally gather his family to tell them the most important truths of their life. On one occasion, a dying man insisted that his lawyer and banker be invited too. When these came, they felt so honoured. Holding them as they stood by either sides of his bed, the old man used his last breath to mutter, “All my life, I have tried to live in the footsteps of our lord Jesus Christ, now that I’m about to die, I would like to die like him, in the middle of two thieves.

On the evening of Holy Thursday, the night before Jesus died, he called together to the Upper Room for the Passover meal his apostles who were his closest associates.

But he acted more than he spoke; action speaks louder than voice. As described in the First Reading of Holy Thursday Mass, at the centre of the Passover meal is the lamb as the symbol of Israel’s redemption from slavery in Egypt.

It was the blood of the lamb slain for the Passover meal, which was sprayed on the doorposts that secured the homes of the Jews as the angel of death passed over their homes to visit the homes of the Egyptians. The Passover meal thus became a memorial of thanksgiving for Israel’s liberation from Egypt but it also expresses the hope of Israel’s definitive liberation – when Israel would truly be free at last.

Jesus celebrated the Passover without a lamb, or rather taking the place of the lamb, he gave himself, his Body and Blood (in the form of bread and wine) in anticipation of his imminent sacrificial death on the cross. Thus, he makes the Eucharist the new Passover.

He is the awaited true Lamb as John the Baptist had introduced him at the beginning of his public ministry: “Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1: 29). For the people, the ultimate liberation of Israel remains political. For Jesus however, it is more of freedom from spiritual bondage to which sin enslaves people.

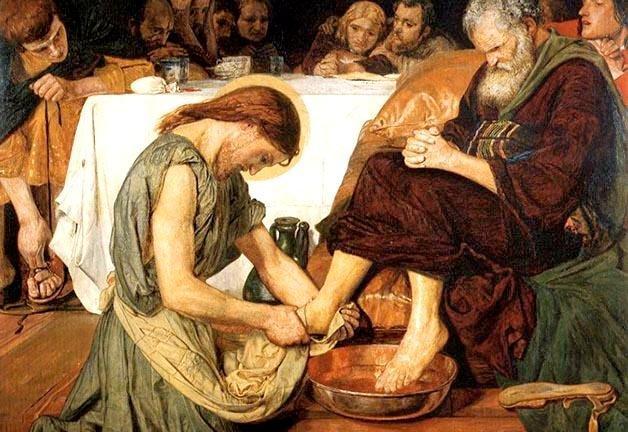

After the new Passover meal (the Eucharist), Jesus used another gesture to profoundly drive home the message; he washed the feet of his disciples and enjoined them to do the same for one another.

So, how do the two rituals relate? Life in Palestine in the time of Jesus was hard. Trekking was the popular means of transport. People walked long distances on rough, dusty roads such that travellers often arrived at their destinations with sore and aching feet. As a sign of hospitality, the host would ensure that the guest was given a warm foot bath and massage as a way of relieving their aches and pains. This was usually done by the house servants or slaves.

This service was also provided at the rest houses or inns located strategically along the major roads and highways. Exhausted travellers could go into these rest houses and have food and foot bath.

Thus refreshed, they are enabled to continue and complete their long journey. That is how such rest houses along the way got the name “restaurants” – they restored strength to tired and exhausted travellers on the way. This is a pointer to the meaning of the Eucharist we celebrate. Understood in light of the washing of feet, the Eucharist is a place of restoration for people on the way.

The life of a Christian in the world is a pilgrimage – a long, hard journey. We can get exhausted along the way and could be tempted to give up. But Jesus has provided us with the Eucharist as a “restaurant” – a place where we can go in to refresh the body and the soul for the journey that is still ahead.

When we give communion to the sick, we call it viaticum, which means “provisions for a journey.” The Eucharist is always a viaticum; in it we derive the strength to continue our journey towards God. That is what every Mass should do for the people of God.

It is a sad contradiction and disservice for people to come out of the Mass distressed. Once, a woman was talking to her priest and noticed he had cut himself shaving. She asked him about it and the priest explains that he was concentrating on his sermon and cut his chin. The woman told him that next time he should concentrate on his shaving and cut his sermon.

The memorial of the institution of the Eucharist goes with that of the priesthood as the two are inseparable.

The Apostles and their successors became the priests who are commanded to continue with the ritual in memory of Christ. Of the priest, the Letter to the Hebrews says that he is “chosen from among men” i.e. he did not fall from heaven but is a human being with a family and a history behind him like everyone else.

It also means that he is made of the same fabric as any other human creature: with the emotions, struggles, doubts and weaknesses of everybody else. Yet, this is deemed as beneficial for others, not a basis for scandal for it implies that the priest, with a sense of his own weaknesses should be more compassionate towards others – a wounded healer.

He is “appointed to act on behalf of men”. Yes, in spite of the broken vows and frequent falls, the reassuring truth is that the ministries he exercises on the altar or in the confessional are not invalid or ineffective because of his flaws; the people are not deprived of God’s grace because of the unworthiness of the priest. It is Christ who officiates at these events; the priest is only the instrument.

Priests are to hold up to sinners an invitation to God’s mercy and not a threat of God’s impending judgment. Today, many are on a crusade to cleanse the church, bent on removing the weeds from the wheat. When we do that, we are playing God (Matthew 13:30).

Our work as priests of God is essentially to reconcile people with God and the best and most effective way to do that is not by being cruel but by being more humane and empathetic recognising that we have been ‘empowered’ by our own weaknesses to be so, otherwise we are being hypocritical. Our prayers should be, “Jesus, meek and humble of heart, make our hearts like unto thine.”