Cycle C | Ordinary Time | Week 26

REFLECTION

– By Fr Ugo Ikwuka

Archway, London

Looking at tombstones, what matters the most is not the boldly written dates of birth and death but the dash in-between. That small hyphen contains our life story. And how we lived is not just about what we did but more about what we failed to do.

What landed the rich man in hell in this Sunday’s Gospel was not what he did. We were not told that he acquired his wealth fraudulently or that he exploited the poor and miserable Lazarus. He did not even abuse or drive Lazarus away. In fact we are not even told that Lazarus begged from him and he refused. All we are told is that he was feeding and clothing well as any other successful human being has a right to do. But as long as that poor man lay dying of deprivation at his feet and he did nothing, he was guilty.

He probably thought to himself that whatever happens to anybody outside his gate is none of his business. Yes, he minds his business, people should mind theirs. Next, he probably phoned the police to report that a stranger was loitering outside his gate. Lazarus being right there at his doorstep means that whenever he steps out or steps in, he steps over Lazarus. Of course he soothes himself with all the excuses that normally play in our heads whenever we ignore beggars: “If you give them money they spend it on drugs.” “Why don’t they get a job like everybody else?”

The poor Lazarus eventually died. The social services came and picked up his body and buried it unceremoniously in an unmarked pauper’s grave. The rich man went in and had another cup of coffee. Of course he had done nothing, but that’s exactly why he would end in hell – for doing nothing! He too dies and is of course given a befitting burial, with uncountable number of Bishops and priests in attendance, each leaves with fat envelope and assorted mix of souvenirs.

Now, notice the irony that while Lazarus was named, the rich man had no name. That is quite significant. A name is a point of connection and contact. That the rich man lacks a name reflects how easily wealth can isolate and wall people off from contact with others. Literally, with wealth comes high security walls, social class and status consciousness which all insulate us from connecting with others. Thus, the torment of the rich man begins here and now in the suffering that comes with isolation. Made in the image of a God that exists in Three Persons – a community of love and sharing, we are meant for relationships – connection with one another and with God. When we lock ourselves in the narrow space of the self, we run counter to our nature in the Trinitarian God.

In torment, the rich man begs Abraham to send Lazarus to quench his thirst. Abraham replies that a gap exists between them that could not be crossed. Then he requests that Abraham sends Lazarus to warn his brothers so that they don’t end up like him. Again, Abraham’s answer was quite cold: “They have Moses and the prophets, let them listen to them…” We should feel the chill because we have Moses and the prophets too. In our First Reading, we hear from the prophet Amos who consistently harps on the isolating danger of wealth, on the luxury of the rich and their indifference to the poor. Are we listening to them?

Yet, we should decode that we are the brothers and sisters of the rich man who get the warning directly from him: “There is finality to life and to life’s choices; the choices you make now have lasting consequences. Whatever you do to the poor, it is indeed to Jesus that you do it. If you establish a gap between the Lazarus at your door and yourself, you are ultimately establishing a gap between yourself and God, and you can only be on the wrong side. Riches are good but they can turn you in on yourself. There is no repentance in the grave. I prayed, pleaded and shed tears but it was too late. Though I had no legal responsibility over Lazarus since I was neither the government nor the social services, it has dawned on me that I have moral responsibility over him.”

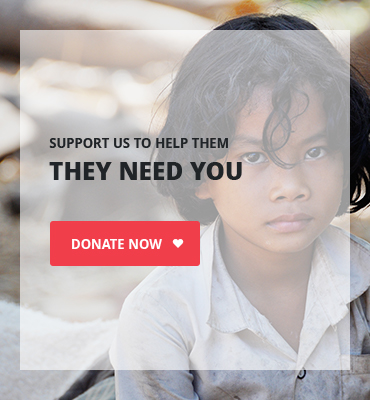

At the global level, today the rich countries of the North sit dining sumptuously at their royal tables in purple and silk with champagne and caviar, while the poor countries of the South are shut out, covered in the wounds of deprivation and exploitation. Can we sincerely heap all the blames on their corrupt systems or on the people being lazy? To a good extent, the wealth of the developed world comes from transactions with the impoverished developing world. Could we dare cross our hearts to say that there is no exploitation going on, perhaps by the very company you work for or patronize?

We live in a world which believes that people deserve everything they are able to work for and acquire. How misleading! To start with, how much hand do we have in the circumstances of our birth which significantly shape our chances?

The foundation of Catholic social teaching is that God is the Lord of creation, hence the owner of all things. We have no absolute right to anything we have. God allows us riches so that our wealth will serve God’s purposes. In effect, we are stewards and the purpose of that stewardship is to cooperate with God’s intention which is the common good. The question of a successful life is not “How much did you make?” but “How did you use what you had constructively for the common good?”

Thus, the parable is not motivated by any resentment toward the wealthy but by a sincere concern for their salvation. God wants to save the rich from their wealth. Yes, the poor needs the rich for a decent living but the rich needs the poor to get them out of hell, out of the torment of self-exiled isolation. Perhaps then, it was an act of God’s providence that Lazarus was there to give that rich man the opportunity to get out of the torment of self isolation. Perhaps the poor around me provides me such opportunity too.